Innovating culture

One theory of culture is that the organisation’s core business, or dominant technology, often gives rise to a pervasive culture. We experienced this in some recent client work: we were designing and facilitating a Top-100 event for a global company, where culture change and the introduction of new leadership behaviours were part of the brief.

As we worked with the internal organisational development team, we were struck by an apparent contradiction: the client’s driving, high ambition for the success of this event and the client’s need to clarify and check every detail to a degree that we as outsiders found excessive and draining. In many consultancies, this might just be a topic for gossip – a difficult client. In contrast, we find these experiences vital to our way of understanding the client’s culture. These micro-dynamics become clues to what it is like in their context, in our client’s shoes. We make sense of these behaviours as a team – what we feel pressurised or pulled to do and what feels off-limits, difficult or dangerous in this system.

The latter is critical. The cultural field impacts your feelings, thoughts and behaviour. Debriefing our experience of being in the client system with a shadow consultant, who is not working on the project, is important to identify the subtle, but powerful, effects of culture. We share the outcome of this sense-making with the client as hypotheses and use the discussion to raise awareness of cultural patterns, tailor how we work with the client system, and in this case used the Top-100 event to accelerate the evolution of the culture.

Two things are critical in how these early hunches are raised:

1. Name and validate the positive impact of the ‘dominant’ mindset and behaviour. In this case, minimising risk, error and unpredictability is critically important to the business, a necessary aspect of managing major technology projects and a source of this company’s success.

2. Inquire with, rather than tell, the client whether this ‘dominant’ aspect of the culture might be inappropriately invading other areas of the business which are non-technical. We highlighted the contradiction: while extreme risk-aversion may be appropriate to executing some major technology projects, it is perhaps unhelpful if blindly applied an event like the one we were engaged with. Uncertainty, ambiguity and appropriate risk-taking are necessary for innovation and, indeed, underpin the company’s desired leadership behaviours.

It’s important to emphasise this isn’t pre-planned consulting: we are improvising with what emerges using a combination of analysis of the situation and our felt-experience of the culture as outsiders. Raising these kinds of observations with the client feels risky as you can be seen to be challenging something that is core to the business and a source of value-creation. It is therefore tempting to go along with the demands and pulls of the culture. We generally avoid that temptation. We use the language and concepts that have currency in the client system to suggest to senior leaders how they can, through a range of interventions, interrupt this pattern of behaviour and reframe thinking.

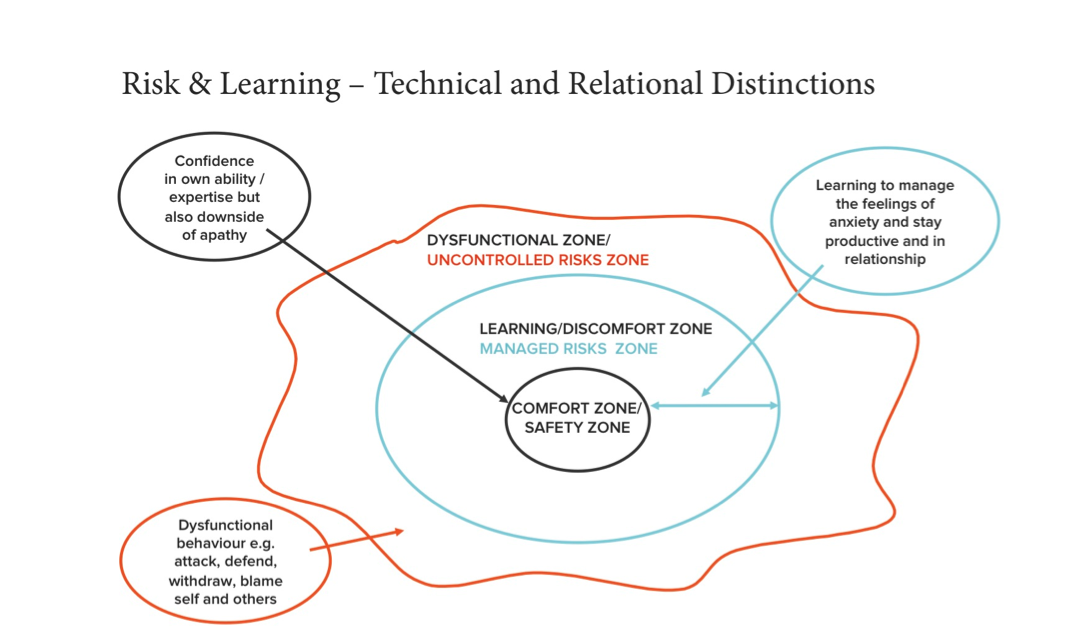

In this case we adapted a simple diagram that describes the emotional zones which apply:

Ordinarily, we refer to the zones as the comfort zone, learning zone and dysfunctional or panic zone. We used this diagram as a vehicle by which senior leaders, who have a key responsibility for holding and evolving the culture, could send a more nuanced and differentiated message about risk-taking. In our conversations with senior leaders we created some distinctions between how risk has to be handled in the technical arena of major projects, on the one hand, and risk in the area of interpersonal relationships and emotional risk-taking, on the other. We explored the role of appropriate risk-taking in bringing to life the client’s desired leadership behaviours. Senior leaders at the event spoke to the necessity of “managed risk-taking” in the context of leadership. Most importantly they modelled these behaviours at the event. Senior executives recognised that the culture encouraged people to retreat too readily into the “safety/comfort zone”. The impact of this culturally-rewarded behaviour was not lost on them: over-engineering, over-consultation and perfectionism were leading to major projects being delivered late, new innovations getting to market too slowly and a cadre of overworked senior managers.

Through our work with this client, we were slowly able to identify areas where people felt it would be appropriate to take more risks. Small experiments emerged, and leaders gained insights into how they could begin to reward new behaviours in their people in order to gradually shift the culture. The event catalysed an evolution in culture.

Changing organisational culture has many similarities with changing human patterns of thought, feeling and behaviour. Take, for example, the sadly all-too-common pattern of someone who grew up with an abusive parent, and learnt to be very guarded, defensive or aggressive as a result. That person might believe this is “just the way they are”. By helping them to understand where their pattern originated – and acknowledging that it was necessary and valuable at some point in their life – we avoid unproductive self-blame or self-justification. It is important to recognise that our stories, beliefs and values (all aspects of culture) are core to who we are, our survival and our success, regardless of whether we are an individual or a global company. Raising awareness about the behaviour patterns that serve us and those that no longer serve us must be done with an appropriate mix of challenge and compassion, affirmation and clarity.

Our work is premised on small steps and an action inquiry approach. It is important that clients experience this new behaviour as producing real benefits and see that the anticipated risks (and fears) do not materialise.

Being appreciative, seeking out and validating the positive impact of the current culture is the first step. Making the invisible, visible in subtle and thoughtful ways is the second step. Taking small steps that interrupt the way things would normally go is the third step. These guiding questions could help begin your journey…

- How could you be a catalyst for evolving your organisational culture? What are the patterns that seem to show up – repetitively and often indiscriminately – in your culture?

- Where did, or do, they serve you? Celebrate this!

- Where do they limit you? What’s the cost?

- How do you, as a leader get caught in these patterns?

- How do you subtly reward and reinforce these patterns – even when they are not helpful to your people or your business?

- What small steps can you take to create a shift towards a broader range of behaviours in your organisation that are more fit-for-purpose?

This article has been written with collaboration between John Watters and Mark Young.