Dateline June 9th 2017, the morning after the UK election. The results of yesterday’s votes are, for the moment, a minority government led by a terminally damaged Prime Minister. Of course, by the time you are reading this, things will have changed further. I am not about to predict how; I prefer you to see that we have left the realms where predictions are any better than guesses. Uncertainty rules. Life is more unpredictable than ever.

But it was predictable that we would encounter such conditions. Over 40 years ago, socio-psychology professor Clare W. Graves predicted we would encounter a transition bigger than any that humanity had faced before. He anticipated where we were headed and he described what it would take for us to cope.

This is not a political analysis. It will begin as a set of observations about the conditions we are now living in and go on to discuss what those conditions call us to be prepared for. The results of yesterday’s votes are, for the moment, a minority government led by a terminally damaged Prime Minister. She is due within days to start Brexit negotiations having failed to receive any sort of mandate and with a portion of her own party calling for her resignation.

In the background are huge shifts. Globally, the Macron and Trump elections gave warning that the old guard is not trusted. The Brexit vote itself signalled a split nation. A Labour party whose name indicates its previous appeal to “the working class” gained much support from the urban middle-class. A Conservative party traditionally seen as appealing to the middle class gained seats through lower class groups in the regions and rural areas. The maps have changed.

In the background are huge shifts. Globally, the Macron and Trump elections gave warning that the old guard is not trusted. The Brexit vote itself signalled a split nation. A Labour party whose name indicates its previous appeal to “the working class” gained much support from the urban middle-class. A Conservative party traditionally seen as appealing to the middle class gained seats through lower class groups in the regions and rural areas. The maps have changed.

Bizarrely, the stock market sees this as good news. An instant fall in UK currency values repeated the scenario of a year earlier; stocks rose because exporters will benefit. It was once the case that markets would react negatively to uncertainty. Apparently this no longer applies.

Of course, by the time you are reading this, things will have changed further. Uncertainty rules. We have to live with that.

But it was predictable that we would encounter such conditions. As I mentioned above, it was predicted in 1974 by socio-psychology professor Clare W. Graves. Drawing his conclusions from a theory that he based on two decades of data collection and analysis, he said that we should expect to go through a transition bigger than any that humanity had faced before. He anticipated by decades where we were headed and he described what it would take for us to cope.

This is not the place to describe the theory, though a very simple version of Graves’ stages of development model may be familiar to those who have read Frederic Laloux or some of our blogs. In this article, I wish to engage with the conclusions Graves reached. In tune with the well-worn observation from Albert Einstein that problems cannot be solved from the level of thinking that created them, Graves described what we would need to learn if we were to thrive amidst the anticipated turmoil.

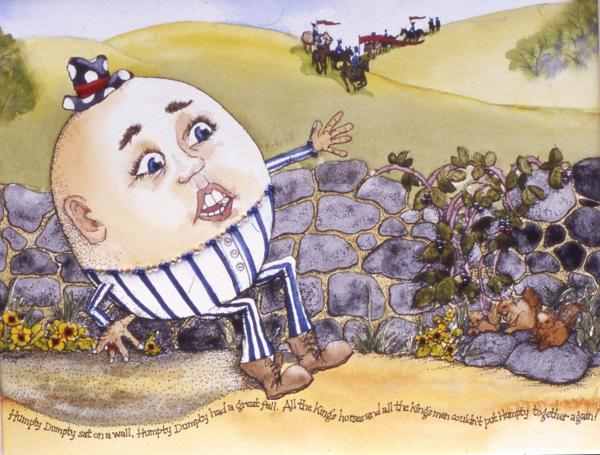

All the Queen’s horses are not going to put Humpty back together, still less set him back on the wall. He has too many cracks in too many areas. Political instability is just one among many and Britain simply part of a bigger pattern of a world in which too much changes, too fast, in unpredictable ways, and where everything is connected to everything else. It’s not a mechanical, fixable system and it has a life of its own.

In organisations, our normal, understandable but regrettably futile response is to want a formula. We look for tried and tested improvement programs with defined outcomes. We believe in evidence-based research with metrics on the deliverables. While that can still have some value – there is always benefit in raising skill levels – it is inadequate in the face of living complexity. While it is scary that there is so much uncertainty and so little control, it does not serve us to pretend it could be otherwise. Theresa May is learning that central control is weak, and so must we.

The ONLY given is change, and the interdependencies of multiple systems and variables are beyond computation. This is not because the issues are mystical and ethereal – they are all too real. It is simply that the variables include people and behaviours as well as interdependencies that are too many and too complex to analyse. You might as well try to find an analytical way to deal with your next case of flu. Your brain can’t do that; a central control system can’t hack it – it requires a response from each cell and organ. Your whole body is an immune system and there is no vaccine against life itself.

If we cannot prevent, cannot avoid, cannot predict and cannot control then we had better learn how to live with it. We need an organisational immune system against life’s unexpected events. The peripheries are as much a part of sensing issues and dealing with them as the central command is. Similarly your skillsets need to be in the muscle memory of the organisation as well as in your cognitive understanding. Being responsive, adaptive and agile is not a nice-to-have. It is fast becoming a condition of thriving and maybe even of surviving.

Humpty was not responsive or resilient. His shell was rigid. He was not that agile either – big head and tiny limbs. Someone must have put him on that wall in the first place. Since we cannot deal with problems from the current level, we must raise our collective game. This does not look likely to happen in the political realm any time soon, but it is possible for leaders and organisations. It is a developmental process and a new skillset, but it is not a formula. It calls for us to take Peter Senge’s concept of a learning organisation to a new level.

It requires the introduction of greater flexibility, autonomy and distributed accountability. It demands the creation of flexibility and flow, with the ability to continuously adapt the process layer. It calls for a mindset of rapid prototyping and an attitude to life that replaces analyse-and-predict with sense-and-respond. It extends Jim Collins’ “Thriving in Uncertainty” and Tom Peters’ “Thriving on Chaos” and makes them a way of living.

Since we are dealing with a new way of being, this is not something that is delivered through a car-wash style training program. Since it is an ongoing, developmental learning process it has to take place alongside and inside real life. The organisation has to learn as it goes, making one adjustment at a time. It is not even a journey, because you can’t know exactly where you will end up. It’s an exploration of uncharted territory in which you create the map as you go. But there are map-making tools, surveying instruments and navigation skills that you can learn. And you can be accompanied by guides who know what this kind of exploration calls for and can help your discovery.

Humpty cannot be put back together again, so it is best not to be one. How do you or your organisation soften your shell and develop more functional limbs? We at Future Considerations have learned a lot about this and we have designed a way of engaging that is appropriately flexible, adaptable and functional. We co-create as we go and model the new world more than teach it. It is exciting work, it can even become fun and you see the benefits from early on. What if there’s a different way of looking at “training and development”? What if the most valuable skill you could learn is adaptability? Contact me if you would like to know more.

Jon Freeman is an Associate of Future Considerations and specializes in systemic organisational redesign in support of conscious, values-led and purpose driven culture change. He is also a Spiral Dynamics trainer and practitioner, and author of “Reinventing Capitalism: How we broke money and how we fix it, from inside and out”.

Future Considerations Ltd

29 Adonis Street, Acropolis

Subdivision, Libis,

Quezon City,

Philippines 1110

Jon’s early career designing applications led to him becoming IT director for a market-leading multinational. His systemic perspective, allied with a background in psychology and subsequent leadership experience inside major organisations was followed by intensive learning in personal development, values systems and multiple intelligences. Brought together, these create a transformational perspective for understanding and developing organisations as living systems. Jon is a master trainer in Spiral Dynamics, a founder director of the UK chapter of Conscious Capitalism and a certified Spiritual Intelligence coach. He is the author of several books and articles and is developer of Relational Being, a visionary whole systems approach to evidence-based spirituality, complexity science, human emergence, societal change and conscious business. This breadth of experience and deep understanding informs his work as a consultant, coach, trainer and facilitator.